Watching a high-speed endurance race and witnessing a 2,000-pound race car suddenly defy gravity, soaring through the air like an airplane before crashing back to Earth in a catastrophic spectacle. This is not a scene from a Hollywood movie but a real-life event that unfolded at the 1999 24 Hours of Le Mans, where the Mercedes-Benz CLR earned an infamous and unwanted place in motorsport history.

Designed to conquer one of the world’s most prestigious races, the CLR instead became synonymous with aerodynamic failure, experiencing not one but three terrifying “flight” incidents over a single race weekend. This article delves deep into the engineering miscalculations, specific track conditions, and tragic legacy of a car that prioritized speed over stability, resulting in one of the most dramatic and alarming chapters in auto racing history.

Mercedes-Benz CLR Design

The Mercedes-Benz CLR was the culmination of Mercedes’ ambitious return to top-tier sports car racing in the late 1990s. As the successor to the highly successful CLK GTR and CLK LM, which had dominated the FIA GT Championship, the CLR was designed to the new Le Mans Grand Touring Prototype (LMGTP) regulations. These rules allowed greater design freedom than the previous GT1 class, notably not requiring any road-going versions to be built. This enabled Mercedes’ motorsport division, HWA GmbH, led by designer Gerhard Ungar, to create a purpose-built racing machine focused solely on performance.

Technical Specifications and Aerodynamic Philosophy

- Engine: A 5.7-liter naturally aspirated V8 (M119 GT108C), producing approximately 600 horsepower.

- Weight: Around 900 kg (1,984 lbs), benefiting from the lower minimum weight allowed in the LMGTP class.

- Chassis: Carbon fiber and aluminum honeycomb monocoque for maximum rigidity and safety.

- Dimensions: 4,890 mm (192.6 in) long, 1,999 mm (78.7 in) wide, with a notably short wheelbase of 2,670 mm (105.1 in) and exceptionally long front (1,080 mm) and rear (1,140 mm) overhangs.

The CLR’s aerodynamic design was primarily focused on achieving a low drag coefficient for high top speeds on Le Mans’ long Mulsanne Straight. However, this pursuit of straight-line speed came at a cost. The car featured a wedge-shaped profile with a low, flat nose and a rear end designed to maximize the effectiveness of its extended rear diffuser. The regulations allowed the diffuser to extend to the very end of the bodywork, and Mercedes exploited this to the fullest, giving the CLR a longer rear overhang than any competitor, 1,140 mm compared to the Toyota GT-One’s 990 mm or the Nissan R391’s 880 mm 1. This architecture, combined with a relatively short wheelbase, would prove critical in the car’s instability.

A Series of Alarming Incidents

The 1999 Le Mans week was a disastrous sequence of events for Mercedes, with the CLR exhibiting its terrifying flight characteristics on three separate occasions.

1. First Incident: Qualifying (Mark Webber)

During Thursday night’s qualifying session, Australian driver Mark Webber was piloting the #4 CLR. As he crested a slight rise on the high-speed approach to the Indianapolis corner, the car’s nose suddenly lifted. The CLR became entirely airborne, flipping backwards before crashing back onto the track and sliding to a halt. The car was severely damaged, but Webber miraculously escaped uninjured. The team rebuilt the car overnight, attributing the incident to a bump on the track.

2. Second Incident: Warm-Up (Mark Webber Again)

Just hours before the race was set to begin on Saturday morning, the rebuilt #4 car, again with Webber at the wheel, headed out for the warm-up session. On his very first lap, the unthinkable happened again. Near the Mulsanne Corner, the car experienced a similar lift, becoming airborne and somersaulting before landing on its roof. The incident was witnessed by photographers and spectators, sending a shockwave through the paddock. Mercedes withdrew the destroyed car but, controversially, decided to let the other two CLRs start the race after urgent consultations and modifications.

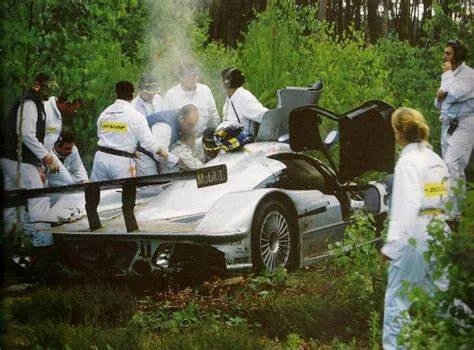

3. Third Incident: The Race (Peter Dumbreck)

Nearly four hours into the race, with the event already underway, Scottish driver Peter Dumbreck was battling fiercely with a Toyota GT-One for the lead. As he accelerated over a slight crest on the Mulsanne Straight at over 200 mph, the #5 CLR’s nose lifted violently. This time, the “flight” was even more dramatic. The car launched completely into the air, flipping multiple times before vaulting over the safety barriers and disappearing into a wooded area beside the track. The dramatic crash was captured live on television, creating an iconic and horrifying image. Dumbreck, like Webber, survived with only minor injuries. Mercedes immediately withdrew its remaining car from the race.

Mercedes-Benz CLR Problems

The CLR’s failures were not the result of a single error but a perfect storm of aerodynamic and design factors that created a recipe for disaster.

1. Pitch Sensitivity and Wheelbase Geometry

The CLR’s fundamental architecture made it uniquely sensitive to changes in pitch (the angle of the car relative to the track). Its short wheelbase (2,670 mm) acted as a pivot point between its very long front and rear overhangs. Under acceleration, braking, or when encountering crests and bumps, the car’s attitude could change rapidly. A small change in pitch would lead to a significant change in ride height at the extreme ends of these long overhangs, drastically affecting aerodynamic performance.

2. The Rear Diffuser and “Center of Pressure” Effect

The CLR’s elongated rear diffuser was designed to generate significant downforce. However, because it extended so far behind the rear wheels, its center of pressure was far rearward. If the car’s nose began to lift even slightly, the rear diffuser would get closer to the ground, generating even more downforce at the rear. This planted the rear wheels firmly and acted like a fulcrum, further lifting the nose in a vicious and self-reinforcing cycle.

3. Loss of Front Downforce and Cockpit Lift

The cars of that era generated relatively low downforce by modern standards, estimated at 2,000-2,500 lbs at 200 mph. The CLR’s front downforce was particularly weak, with a “muted front diffuser.” When driving in the turbulent air (“dirty air”) of another car, this already limited front downforce was drastically reduced. Furthermore, the closed-cockpit design inherently generated lift from the “cockpit bubble”, the curved canopy. Under normal circumstances, the car’s downforce would counteract this, but if the nose lifted and the underside stopped working, this lift became the dominant force.

4. Triggering Events: Crests, Curbs, and Traffic

The incidents were triggered by a combination of factors present at Le Mans:

- Track Topography: The slight crests and undulations on the Mulsanne Straight were enough to momentarily change the car’s pitch.

- Traffic: In each incident, the CLR was closely following another car. This ran in the lead car’s slipstream, which robbed the CLR’s nose of crucial downforce.

- Suspension Setup: Reports suggest the team was running soft rear springs to improve straight-line speed by reducing drag, which may have exacerbated the pitch sensitivity and made the car more prone to lift-off oversteer and nose-lift.

Table: Key Design Comparisons of 1999 LMGTP Cars

| Car Model | Wheelbase (mm) | Rear Overhang (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Mercedes-Benz CLR | 2,670 | 1,140 |

| Toyota GT-One | 2,850 | 990 |

| Audi R8C | 2,700 | 940 |

| Nissan R391 | N/A | 880 |

1999 LeMans Crash Aftermath

The immediate aftermath of the race saw Mercedes-Benz immediately and permanently cancel the entire CLR program. The company withdrew from sports car racing entirely, a decision undoubtedly influenced by the desire to avoid further reputational damage and the haunting memory of the 1955 Le Mans disaster.

Emergency Modifications and Missed Warnings

After the first two incidents, the team consulted with renowned F1 aerodynamicist Adrian Newey. On his advice, they hastily attached front nose dive planes to the remaining cars before the race. Mercedes claimed these added 25% more front downforce, which would have been a significant improvement. However, these last-minute fixes were insufficient to counteract the fundamental design flaws that were revealed in the worst possible way during the race.

LeMans Regulatory Changes

The CLR’s flights had a profound impact on motorsport safety:

- Circuit Modifications: The ACO (Automobile Club de l’Ouest), which organizes Le Mans, made alterations to the track surface to smooth out the crests and bumps that contributed to the incidents.

- Aerodynamic Regulations: The rules governing the dimensions and placement of diffusers and bodywork were tightened. Scrutineering of aerodynamic stability, especially in relation to lift-off oversteer and pitch sensitivity, became far more rigorous.

- Car Safety: While the CLR itself was strong, as evidenced by the drivers’ survival, the incidents highlighted the extreme risks of aerodynamic instability. This pushed teams to prioritize stable aerodynamic platforms over outright low-drag performance.

Leave a comment